Versailles, France

The central character of this comedy is definitely Tchatski. As a man of spirit, Tchatski is doomed to walk on fine lines. This is the woe of wit, the woe of men doomed to wander in infinite fields.

Travelling through lost paths

in the infinite fields, we linger without doing anything

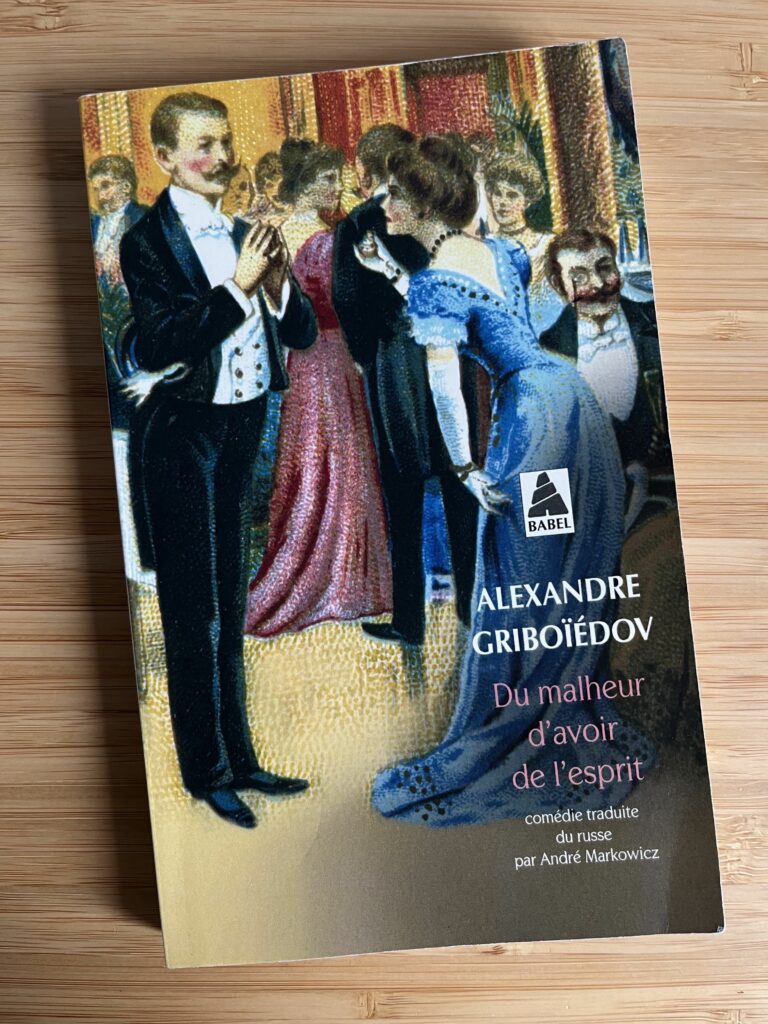

Woes of wit, Alexander Griboyedov

More than the satire of the nobility, more than the countless proverbial lines, more than his desperate love for Sofia, more than the critique of what the word-less and substance-less Moltchaline represents, more than the very immediate historical context (Byron is fighting in Greece, the december coup is on its way), the marvel of this comedy lies in Tchatski’s embodiment of eternal dilemmas.

Should we borrow ideas from abroad ? Should we stay true to the one sacred identity ? Should we borrow ideas from abroad, only to revive the one sacred identity ? This is a fine line to walk on.

Tchatski is a man of culture and books, a man of beauty and art among men who see science and instruction as a plague (Famoussov). He craves freedom and refuses censorship, but he is no man of club reunions, and seemingly no man for the day of the storm (or revolution). Tchatski wants to serve, but not to be someone’s servant.

Tchatski walks that fine line between passion and headless passion, or action, in other words.

In his rejection of French influence and overall Peter the Great’s european turn, Tchatski comes to question whether China wouldn’t be a more palatable influence :

Our Russia is a hundred times less beautiful

I am an old believer, so be it

since Russia traded its customs, its language, its sacred past

if we are born to always borrow

why not borrow from China

Woes of wit, Alexander Griboyedov

This thought of Tchatski has as much historical reach as Alexander Nevski’s dilemma in Eisenstein’s masterpiece movie : fight the Golden Horde or the Teutonic Knights ? East or West ?

Yet for all his rejection of French influence, Tchatski ends up being called a Voltairian and a Jacobin, references he would certainly have done without.

The cruel irony of ideas and impossible quest of the one pure idea.